We recently returned to our discussion about antiracist research methods, and want to open a new dialogue about how we at DataWorks can engage with data in an antiracist way. In this blog series, we ask ourselves: “in what ways do we think about data that we may not even realize are racist?”

In this post, we’re thinking about data sources and their historical context.

Decontextualized data

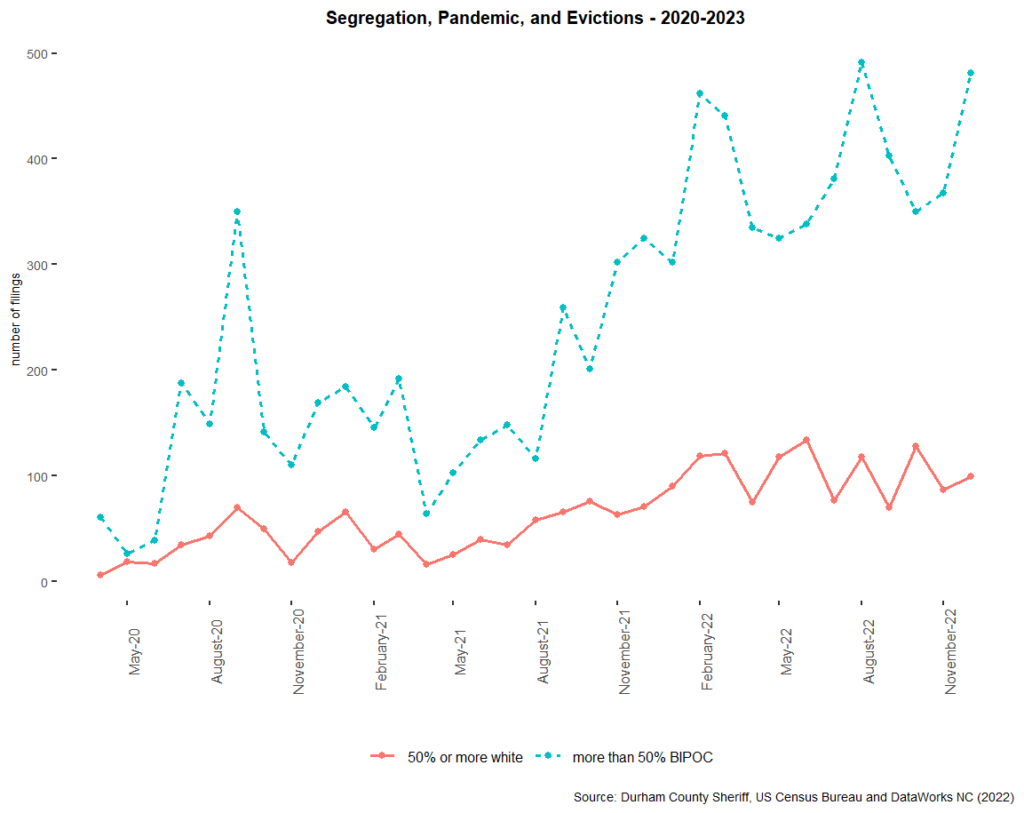

The chart below without historical context shows racial disparities in evictions following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. This decontextualized data leads to a common interpretation that COVID-19 created racial disparities, when in reality, it just put a magnifying glass on the legacy of systemic racism.

Historical context

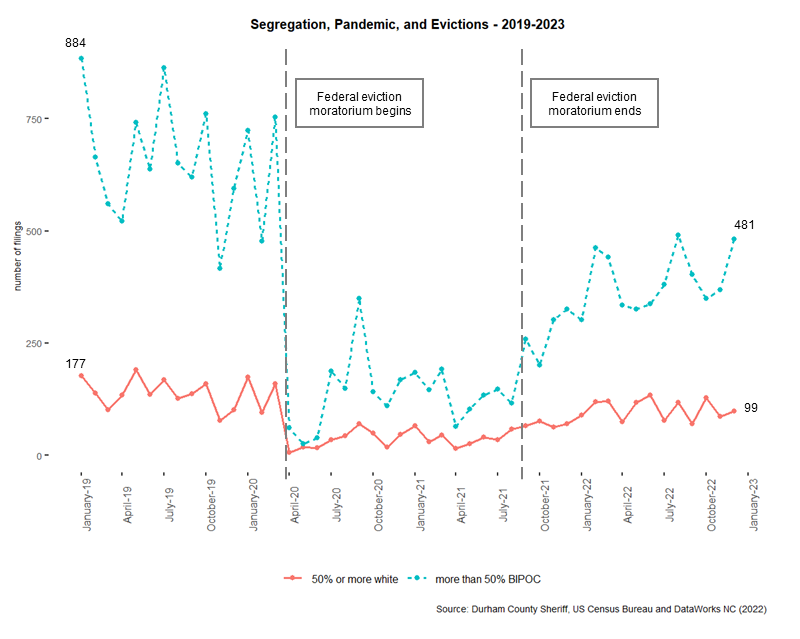

A single phenomenon like the pandemic is not what produces disparate outcomes. As you can see in the chart below, the number of eviction filings in January of 2019 in block groups of more than 50% people of color was approximately 80% higher than filings in block groups where 50% or more were white. Housing as a system in America shows that the disparities long precede individual crises – and there’s a deep history underlying that. In Durham (whose story is not unique in US cities), our system of property ownership is established through land grants starting in the 1600s on land stolen by white settlers. Many tools of white supremacy recreated segregation over the decades through plantation dominated land use, racial restrictive covenants, sanctioned loan discrimination, urban renewal, city-supported gentrification (hear a more complete history of segregation in Durham from John Killeen).

What are the data sources documenting structural racism?

Surveys

Survey questions often focus on individual behaviors when addressing racial disparities, particularly regarding structural determinants of health. A DataWorks focus group participant addressed the problem succinctly:

These reports don’t address root causes and completely miss the mark. These are all important things to address, but we need to tackle the foundation in order to resolve the issues. People put bandaids or low-hanging objectives that can be checked off, but needs to be levels deeper.

(Report on Community Conversations on Racism & Health)

Contextual Data

Our recommendation is to use contextual data sources to convey instances of structural racism. The many ways in which structural racism manifests in housing access offer several salient examples for Durham. While racism in housing can operate at many levels, one example of structural racism in housing is racially disparate eviction rates, as shown in the charts above.

What can we do better?

- Start with history

Events like the pandemic offer an opportunity to reckon with our legacy of structural racism, but addressing the current issues without historical context will not fully address the root causes of disparities.

- Listen for community concerns

Let concerns from the communities most impacted inform the solutions. The COVID-19 eviction moratoria were perhaps the most impactful housing policy interventions for tenants in US history. This is because it eliminated a root cause (eviction) of multiple intersecting disparities (in education, employment, wellness, etc.).

- Let that define what data to use

Trust people to know what they need. Contextual data help avoid burdening survey participants with potentially trauma-inducing survey questions and provide historical awareness.

Leave a Reply