“Seven of us received eviction notices this week.”

These were the sobering opening words spoken at a meeting with leaders from the Hoover Road Community on July 25, 2019. Durham CAN’s (Congregations, Associations and Neighborhoods) lead organizer, Atinuke (Tinu) Diver, had planned that evening’s meeting to be a mini workshop about collective power. Instead, it turned into the beginning of our work on the Durham Housing Authority’s eviction policy.

The Hoover Road Community

Hoover Road (HR) is a Durham Housing Authority (DHA) property located in East Durham, north of the 147 freeway. The community has 54 townhome style units housing 123 people. About half are school-age children. Ninety-eight percent of the heads of households are people of color. Ninety-eight percent earn less than 30% AMI.1

That August meeting was a follow-up to a listening session with HR residents that Durham CAN leaders facilitated on July 16. The top concerns expressed were chronic and unaddressed maintenance issues, safety, and lack of activities for children in the community. HR residents made plans that evening to inspect the units and submit the results with photos to the CEO of DHA.

With that in mind, our initial reaction to hearing about more than 10% of households receiving eviction notices was that it was retaliation for attending the listening session. We soon came to realize, however, that large numbers of eviction filings by DHA each month was the norm.

The Entire Eviction Process is Harmful.

Throughout this post, I will be talking about eviction filings, which comprise the first stage in the process of eviction and are not Writs of Possession. A Writ of Possession is a court order that orders the Sheriff to evict the tenant.

We believe the eviction filing itself, even if voluntarily dismissed by DHA in the courtroom, is very harmful for several reasons, including the court fees passed on to residents, and the fact that filings stay with residents for life and could prevent them from finding alternative housing.

In talking with residents who were comfortable sharing their experiences with us, we heard about erroneous filings where the resident received an eviction notice despite having the receipt for the money order for the paid rent.

We heard about the inaccessibility of payment locations and rent statements not being delivered.

We heard about the challenges of showing up for court when relying on public transportation.

We also heard about the $126 filing fee that DHA passes on to residents. Given that average monthly rent for DHA units is around $240/month, 30% of household income, a bill for $126 on top of a $15 late fee is excessive, especially when you consider that a lease goes both ways. There are real habitability concerns with many of DHA’s public housing units and several DHA communities have a history of failed physical inspection scores.2

In the Courtroom

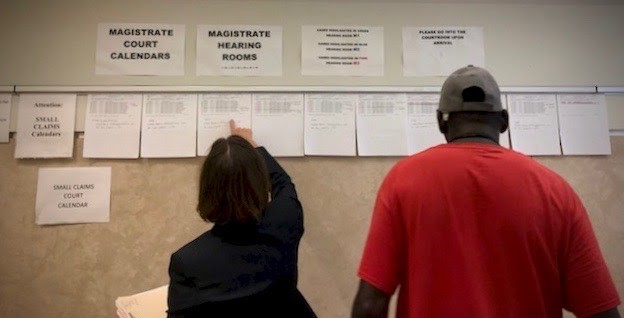

In August, we began observing DHA’s eviction hearings. Initially, we simply wanted to support HR residents, but it turned into a regular practice of court watching. On a typical hearing morning, a group of around five of us meet in the lobby of the Durham County Courthouse and go up to the third floor together where the Magistrate Judges hear cases.

In the courtroom, we simply observe or take notes. Not only have we been able to meet residents from other DHA properties and hear how eviction filings affect them, we have also gotten a sense of other variables: that cases in which the resident has representation (usually by Legal Aid) have better outcomes; that different judges approach cases differently; and the fact that the amount of money owed is often as little as $50.

Our persistent presence in the courtroom has gotten reaction from both the judges and DHA’s General Counsel with the latter inviting us to a meeting.

Putting DHA Evictions in Perspective

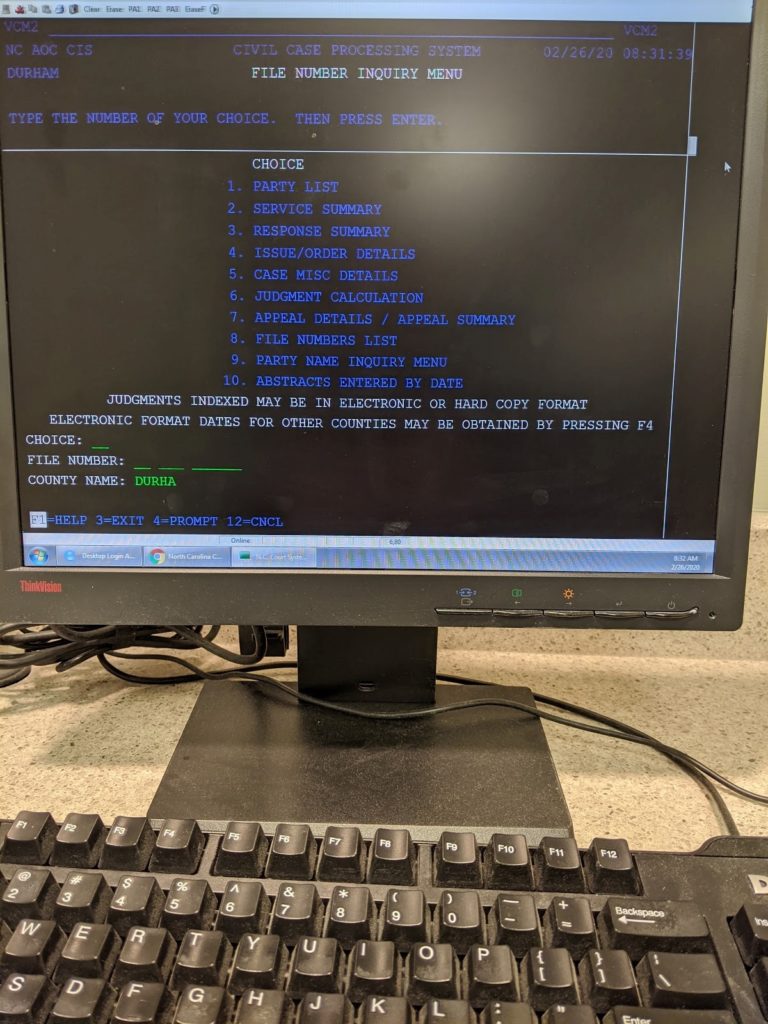

To get a historical perspective of the numbers of evictions that DHA filed in 2018 and 2019, we used the public terminals located in the Civil Claims Division on the first floor of the courthouse to collect data.

You can search by party name, file number, and even date. The data available include date of the eviction filing, the hearing date, name, and the outcome of the case, whether it was dismissed, denied, or granted.

Sometimes, appeals are made and that information is available too, although it was not the focus of our research. The raw numbers each month were of primary interest, but the outcomes of each case on a monthly basis offer insight on differences in how the cases are heard. For example, some months show large numbers of denials by the Magistrate and other months show a larger percentage that are granted.

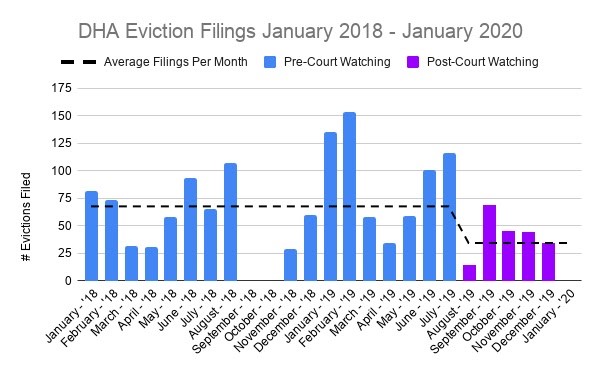

The graph above shows the data we collected for 2018 and 2019. Each bar represents the number of evictions filed during the month. The different colors of the bars offer a pre/post court watching comparison with blue representing the pre-period and purple representing the post-period.

Note that there is a one-month lag between when the evictions are filed and the court date; so, our first month of court watching, August, we heard the 116 evictions filed in July. There were only 14 cases filed in August which we attribute both to an announced change in DHA eviction policy3, and a request we made for a temporary moratorium on evictions at a meeting with HR residents, Durham CAN leaders, and the CEO of DHA on August 22.

The dotted line indicates the average number of filings per month calculated separately for the two periods. The decline in average number of filings per month are likely due to a combination of factors: an increase in Legal Aid tenant defense, court watching, demands like the moratorium, and the DHA policy change.

Continuing the Work

It was Durham CAN’s discipline of community organizing that brought us to the eviction issue. Without the trust built with residents of HR, we would not have started down this path. The work has offered Durham CAN leaders many ways to engage on the issue through court watching, the meeting with DHA’s General Counsel, data collecting, and data analysis. We continue to monitor DHA eviction filings and have made requests of DHA to offer restitution on filings they voluntarily dismissed and to make permanent the Eviction Prevention Pilot, a pilot program to further reduce evictions.

1https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/assthsg.html

2https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/pis.html

3https://www.durhamhousingauthority.org/about-dha/press-room/2019/216/

Heather Ladd is a Statistician living in Durham. She is a member of Durham CAN through the Eno River Unitarian Universalist Fellowship.

Atinuke Diver serves as the Lead Organizer and Executive Director of Durham CAN.

Ruth Petrea lives in Durham and is a retired public school teacher. She is a member of Durham CAN through her church Trinity Avenue Presbyterian.

We would like to acknowledge and thank the residents of the Hoover Road Community, a Durham Housing Authority property. This work would not have been possible without their courage and trust.

Leave a Reply