I’m the health data analyst with DataWorks and a PhD student in epidemiology at UNC-Chapel Hill. I’m using these posts as space to reflect critically on my dissertation, a collaborative project with the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network and the Concerned Citizens of West Badin Community which assesses race and gender disparities in work exposures and health at an aluminum smelting facility in Badin, NC. Through this collaboration and other projects I’ve participated in, I’ve learned how research can be a powerful tool for highlighting community concerns, and how it can undermine organizing efforts.

What are “Racist Research Methods?”

“That the founder of statistical analysis also developed a theory of White supremacy is not an accident. The founders developed statistical analysis to explain the racial inferiority of colonial and second-class citizens in the new imperial era.” – Tufuku Zuberi and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva describe dominant social science approaches, polluted by white ideologies, as “white methodologies” in their book, White Logic, White Methods: Racism & Methodology.

1. Research Used to Justify Harms

Health research, in particular, can be used to justify harms. One of the ways in which this is manifested is in race-based clinical metrics. There is a growing dialogue around the misuse of science in medicine, perpetuating arguments used to justify slavery and conflating race with genetics. I’d argue this problem is especially pervasive in occupational epidemiology.

Black scholar Cedric Robinson coined the term “racial capitalism” to describe race as a central operating logic of the political, economic and social system of capitalism. In other words, racism against Black communities is the engine that allows capitalism to grow, not only in slavery, but even in 20th and 21st century industrialization.

Through my work in Badin, I have heard medical doctors endorse statements like “Black people have smaller lungs than white people” and company supervisors claim that “Black workers were hired into the smelter out of sharecropping because they were better able to stand the heat.”

I think these exemplify racial capitalism because the function of the industry relies on maintaining fundamentally unequal races. In Badin, this was executed by pathologizing Blackness itself. In other settings, disparities are explained by behaviors, typically ignoring the historical, social and political structures giving rise to the disparities.

2. Research That Forces Impacted Groups to Prove Harms

Causal inference has set up a structure in which people are asked to prove health impacts of clearly harmful practices with “objective” science.

We see characteristics of white supremacy, explicitly described by Tema Okun, perpetuated in occupational epidemiologic methodology when company-run studies claim objectivity and indicators of community health are measured by “days of work missed.” I’ve started my dissertation by identifying three major limitations in the scientific literature on aluminum smelting and worker health. These lead to research that does not:

- Capture the full set of hazards with a narrow focus on company-initiated interventions (e.g., hearing protection) and methodological advances;

- Document race and gender disparities in exposure/health;

- Reflect worker experience described by former workers in West Badin.

3. Research That Doesn’t Respond to Community Concerns

Traditional health research also shifts the dialogue to focus on questions that are not generated by the community and studies that are conducted on the community rather than with it.

I’m guilty of participating in this traditional, top-down, extractive research. I worked in Boston for 5 years with Boston Medical Center (BMC) and several community health centers affiliated with the Health Network. Our research focused mainly on housing access and neighborhood safety. We did a lot of positive work—connecting families to resources, and building networks of community organizations focused on housing.

We also did a lot of work I consider to be problematic, and that was reflected in community feedback. “Our” data was health records of individuals receiving care, publicly available census data, and administrative data from the police and urban planning department.

“I wish you all would stop coming in here and showing me what’s wrong with my neighborhood.”

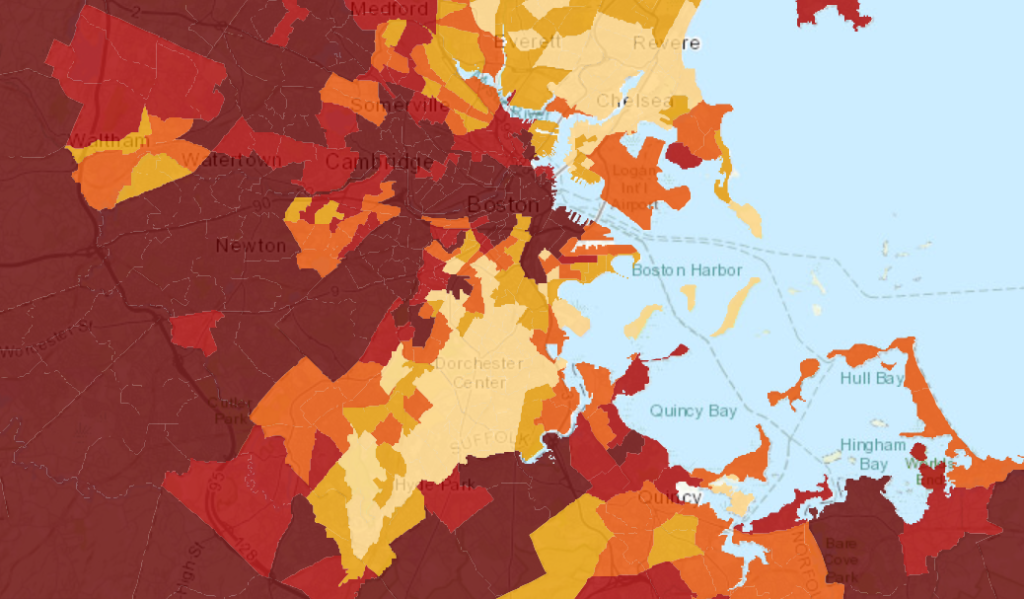

We brought maps like this one, which shows childhood obesity rates (lighter colors representing higher rates), as well as maps of hypertension, crime, and homelessness to neighborhoods near BMC. At one meeting, a woman raised her hand and said, “I wish you all would stop coming in here and showing me what’s wrong with my neighborhood.” I try to carry that thought with me as I enter new projects and spaces.

I most recently acted as the analyst on a study really similar to my Boston work. This study, which was regrettably somewhat disconnected from the community, assessed the relationship between built environment interventions (like bike and walking paths) with childhood BMI in Durham. What I did like about the project is that we began to complicate this pretty standard public health research question by looking at differences in effect by gender, race, and socioeconomic status. We encouraged readers to ask: who do these trails benefit? Who do the interventions overlook? In this way, the project also provides a starting point for community conversations.

I’ve talked here about three of many ways in which research methods can be racist. These are well-documented in the scientific literature and public dialogue, and they are continuing to emerge. Opportunities to do better, to conduct antiracist research, are less discussed. Learn about some of our ideas for antiracist methods in the next post in this series.

This is part 1 of a 3-part blog series that examines the relationship between research and community organizing.

Research and Community Organizing Series:

Part 2: 3 Ways to do Anti-Racist Research

*

Libby McClure is DataWorks’ health data analyst and a PhD student in epidemiology at the UNC-Chapel Hill. Her work is focused on the ways in which historical and structural inequalities produce health disparities.

Leave a Reply